Some Notes on Drawing

=====================

<!--

Copyright (c) 2017 Chris Pressey, Cat's Eye Technologies.

SPDX-License-Identifier: CC-BY-ND-4.0

-->

* publication-date: Oct 2017

When I was very young, I asked my parents what you called someone who draws. Their

answer was "a drawer". I was deeply upset, not to say offended, because to me, a

drawer was a kind of furniture. They agreed that it was, but stood by their statement,

hiding behind the fact that words can have more than one meaning.

Perhaps they did not know, or wish to use, the word "draughtsman". While it does seem

to be a word that's less regularly used in North America than in the UK, this would

have been a time when it was the name of an actual profession — and before there was

any pressure to use a gender-neutral term such as "draughtsperson". Which is such an

ugly word that, y'know, "drawer" doesn't seem all that bad.

Some people claim they cannot draw. This is a lie. Everyone can draw; this is

amply attested by UFO eyewitness reports. (These are also strong evidence that

very large objects are most naturally measured in terms of football fields.)

If someone says they are not a good drawer, that is closer to an honest statement,

but it still presupposes that there is such a thing as a "good drawing", and further,

that they can distinguish a "good" drawing from a "bad" one. (Yet ask them to do so,

and they will probably beg off, saying they're no art critic. So frustrating.)

I think it would be more accurate still to say that a lot of people simply do not

like *how* they draw.

The artworld does not hold drawing in high regard. It's not like that most-favoured

child of the artworld, oil painting, oh no. Let us now recoil in horror in unison

over the fact that *mere children* do it.

I would like drawing to be held in higher regard than it is. Mathematics has been

called "the queen and the servant of the sciences", because it is both fantastically

useful to each branch of science individually, and grandly unifying to the sciences.

Perhaps we could say something similar for drawing, that drawing is the queen and

servant of the arts. Not just thumbnail sketches and underdrawings for paintings,

but also architectural drawings, dance diagrams, set designs, fashion drawings...

Methods of Drawing

------------------

There are three basic ways of drawing anything: from life, from a reference, and

from the imagination. Each of these ways has their own advantages and disadvantages,

their pros and cons.

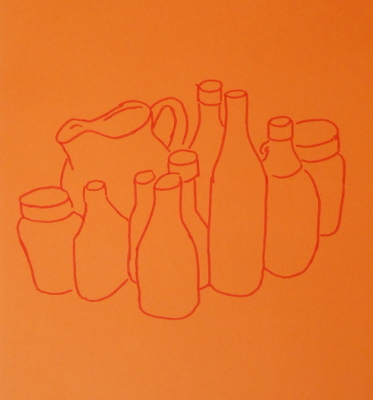

### Drawing from Life

You are drawing something "from life" if that thing is right in front of you, even

if that thing is dead. [(Footnote 1)](#footnote-1) I suppose, then, that in this

context, "life" refers to the drawer's own life.

Drawn this way, the result will itself usually have more "life" in it. Critics use

fancy art-words like _brio_ or _élan_ to describe this. I cannot begin to explain

why this is, so I won't. But it's true. If you go over such a drawing in, say, ink,

after making it, you will almost certainly "deaden" it.

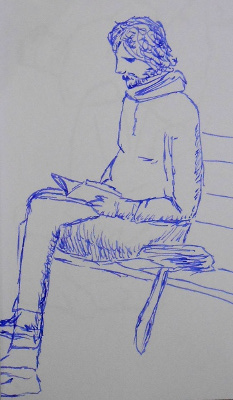

Of course, you can make it in ink to begin with, if you can live with the idea of

not being able to erase it. Such a drawing can be called a _sketch_, in a specific

sense of this word that it has in the context of drawing, where scholars think it

came from the Italian word _schizzo_ meaning "to spray". It means, roughly speaking,

making multiple not-necessarily-accurate lines and relying on the viewer's eye to

"split the difference". It would be the opposite of _line drawing_, which is usually

interpreted to mean that the lines are clear and are the "right" lines.

But even this is a bit oversimplified. A line, on paper, usually indicates an outline,

which itself is an abstraction of a "boundary" in reality where one thing

(e.g., an apple) stops and another (e.g. a bowl) begins. But it need not be that, in

two ways. First, lines, especially when closely spaced and at consistent angles,

can represent a _texture_ to the eye. Second, a "misplaced" line may very well

harmonize with the overall composition and go virtually unnoticed by the viewer —

at least until they begin examining the picture more closely. Such "mistakes"

are rarely as bad as a beginning drawer assumes they are. The eye can actually

tolerate quite a lot of "error" in lines, so long as there is an overall composition

holding them together.

And anyway, there's nothing saying you need to make _lines_ when drawing; it's just

one of the more convenient things a pointed stylus can do. You may have also noticed

that the edge of the pencil can shade an area. And various media can be "washed" by

adding some water to them. There is even washable graphite, and I like the idea of

washable graphite a lot, because it makes it difficult to say for certain whether I'm

drawing or painting.

Because it captures "life" so well, there are some that consider drawing from life

to be the only "real" kind of drawing. The disadvantage, of course, is that if

what you're drawing is moving, you have to be quick (or have good short-term

memory) or, if it is sentient, convince it to try not to move while you draw it.

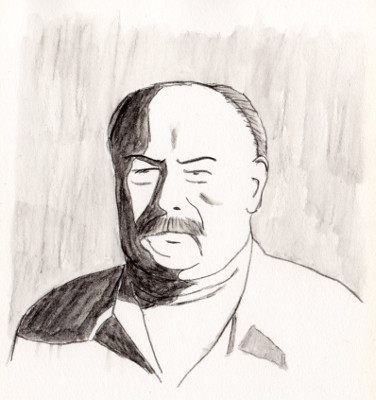

### Drawing from a Reference

Often the reference is a photograph, although it could also be another drawing.

This solves the problem of the subject moving quite well. Many portraitists

will tell you, though, that a portrait from life captures a superior likeness of

of the sitter exactly _because_ they move: the portraitist "integrates over"

their angles and expressions, while a photograph only freezes a single instant

in time from a single perspective.

But going without that might be worth it, if it means one less person is

asked to sit still for a half-hour. Because, have you ever tried it? It's

actually pretty torturous. Artists' models deserve more respect.

Anyway, when drawing from a reference the trick is to avoid slavishly copying

the reference. This is harder than it might sound.

Taking this idea to the extreme is _tracing_, where the reference is below the

(thin) paper you are drawing on, or projected onto a surface by a projector, etc.

Some people will call this sort of drawing from a reference "cheating".

This, too, is a lie, because in order to cheat there first needs to be a rule

that can be broken. It would be more accurate to say that this usually results

in a stilted, dead-looking drawing.

But even so, that's mainly because when you make a tracing, you usually hunt for

what you think is an outline in the picture, and make a drawn line out of it.

There are two problems with this. One is that when someone else sees that line,

they don't necessarily recover the same outline you (thought you) saw when you

traced it. In fact they usually don't. The other is that not all boundaries

between things reduce well to lines. The human nose, for example, is notorious for

this — it's quite difficult to depict it well with only lines and no tone.

*If* you realize these things and consciously try to counteract them when tracing,

you can possibly mitigate them. But this is still very difficult, and might not

be worth it; developing a good sense of "eyeball measuring" is not much more

difficult, and more useful.

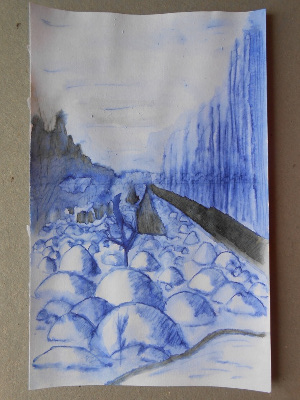

### Drawing from the Imagination

William Blake was big on this. Piranesi and Tiepolo, too, and Leonardo too, for

that matter, because _invenzione_ was big in the renaissance. More on that in a

second.

People will sometimes say "drawing from memory" instead of "from the imagination",

especially academics. Probably because the latter sounds fanciful and thus

vaguely unprofessional somehow. (I refer you again to the horrifying fact that

*mere children* have imaginations.)

And I mean, technically I can see what they're getting at — you can't draw a

horse unless you've seen a horse sometime in the past, right? — but referring to

the imagination still seems more accurate. It's not like those [Imaginary Prisons][]

are things that Piranesi actually *remembered*. Well — unless he dreamed them.

I don't know that he didn't.

Also, I don't remember where I picked this up, but someone pointed out that if

you look down at your drawing while you are drawing it, as most drawers do, *all*

drawing, even drawing from life, is technically drawing from memory. That's maybe

a pedantic point, but it's worth thinking about: having a good short-term memory is

helpful. There are probably exercises for developing this, I don't know.

Anyway, what I was getting at is, memory is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition

for imagination. I have to remember what a horse looks like, and what a horn looks

like, but I have to imagine what a unicorn looks like.

Unicorns! Don't get me started on unicorns. They're a philosophical aesthetician's

absolute favourite animal. [(Footnote 2)](#footnote-2) Because a drawing of a

unicorn isn't a *representation* of a unicorn, you see, because they don't exist,

you see, and you can't *represent* something that doesn't exist, you see, and

determining what a picture *represents* is very important in the world of

philosophical aesthetics. And I know they don't exist because I've visited every

planet in the galaxy and I've never seen one on any of them.

The main drawback of drawing from the imagination is, of course, that it's easy to

get basic things wrong. By "basic things" I mean, the relative length of limbs of

a figure, or the foreshortening, or sometimes even the number of digits on a hand,

for goodness sake. And even if not outright _wrong_, for something as complex and

subtle as the human figure, it's almost inevitable that the drawer will miss some of the

subtleties, like the way the muscles flex when a heavy object is being held versus

when one's hand is empty. The result is a picture that looks "off" somehow — and

it's usually hard to say exactly what is wrong because it is only that the visual

cues don't add up.

For this reason, some would call drawing from the imagination, especially drawing

the human figure this way, the ultimate test of an artist. I don't know, but I agree

that it certainly is difficult. As I said, _invenzione_ — making *up* your drawing

instead of representing something that already exists — was big in the Renaissance.

Tiepolo's [Capricci and Scherzi di fantasia][], for instance, are arrangements of

figures and scenery which seem essentially random; he might as well have been

rolling dice to determine their composition.

[Capricci and Scherzi di fantasia]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Battista_Tiepolo#Etchings

[Imaginary Prisons]: http://artmuseum.princeton.edu/object-package/giovanni-battista-piranesi-imaginary-prisons/3640

### Discussion

These three methods aren't intended to be perfectly hermetic. Drawing from a

sculpture (a traditional part of academic art instruction, before moving on to

a living model) could be either drawing from life or drawing from a reference,

depending on how the drawer treats it, while drawing from one of those little

artist's mannequins that IKEA now sells as furnishings would probably be a

combination of drawing from a reference and drawing from the imagination.

But I do think it is a very useful division. And obviously, it applies to

painting, too.

And actually, once you know about the division, you start to notice it.

For example, Cézanne was big on painting from the imagination, and

[you can really tell sometimes](http://www.paulcezanne.org/the-judgement-of-paris.jsp).

Similarly, later in his career, Picabia made a lot of paintings from photographs, and

[you can really tell with those, too](http://www.artnet.com/galleries/michael-werner-gallery/francis-picabia-late-paintings/).

Photographs are far more unforgiving about lighting than the human eye is.

A word on technique. A tradeoff that applies to all of these methods is that

if you make a mark too slowly, it looks "fussy" — too deliberate, somehow.

But the faster you make a mark, the more likely it will be inaccurate. The

only way out of this tradeoff is to make accurate marks quickly.

And, just the same as e.g. handling a bow and arrow, the only way to be both

fast and accurate is to have a lifetime of practice.

I remember reading something written by students of Mervyn Peake, and they

were consistently impressed by his _confidence_ of line. That's probably

exactly what I'm talking about here.

Of course, even here there is an exception. If _all_ the marks look very

deliberate, and enough care is taken with them, the drawing can then look

"worked" — almost like a painting. Whether this is a good thing or a bad

thing seems to be largely a matter of taste.

Books

-----

I've read a number of "How to Draw X" books, of course, but they don't tend to

go into much depth. (Deconstruct the subject into a number of tin-cans. OK.

Try different media and grounds until you find what you like. OK, OK...)

It wasn't until I encountered these two books that I felt I had really found

studies of drawing _per se_:

### Seeing through Drawing

* authors: Philip Rawson

* subject: Art

* release-date: 1979

* ISBN: 0563173963

* publisher: BBC Books

### Drawing Acts: Studies in Graphic Expression and Representation

* authors: David Rosand

* subject: Art

* release-date: 2016

* ISBN: 1316637522

* publisher: Cambridge University Press

Footnotes

---------

##### Footnote 1

Indeed, the French translation of "still life" is _nature morte_, which

literally translates to "dead nature". Go figure.

##### Footnote 2

I have to say "philosophical aesthetician" because a just plain "aesthetician"

is someone who does your nails, which is not what I mean, while an "aestheticist"

is an adherent of Aestheticism, which is also not what I mean. Even though some

of these people may in fact like unicorns a lot too.